This week, I choose Rolfe et al.’s (2001) reflective model, which is based upon three simple questions: What? So what? Now what? This is about the indigenous knowledge and cultural responsiveness in my practice

What?

Indigenous knowledge is referred to the funds of

knowledge and expertise that students and their families and whanaus are having

which directly related to their lived experiences within their cultures

(Gonzalez, Moll & Amanti, 2005). And, Gay (2010) defines culturally

responsive pedagogy as teaching ‘to and through students’ personal and cultural

strengths, their intellectual capabilities, and their prior accomplishments’ (p.

26) and as premised on ‘close interactions among ethnic identity, cultural

background, and student achievement’ (p. 27).

In my own experience and understanding, ‘indigenous

knowledge’ is the students’ personal and cultural knowledge and ‘cultural

responsiveness’ is about the recognition and inclusiveness of every student

culture in all aspects of learning and teaching. As a teacher, I am leaning

more to cultural responsive pedagogy which gives me the opportunity to build a

very strong foundation of relationship with my learners and their whanaus. And

I am aware of it and trying to recognise and celebrate my students’ cultures in

my practice always boosts up their confidence in knowing who they are which

motivates them to do well. Indigenous knowledge

and cultural responsiveness should be prevailed in both areas, (1) school-wide

activities and (2) learning activities.

So what?

I currently work at

a multicultural mainstream school (in Papatoetoe) where Pakeha and Maori are the minorities in our school roll,

whereas the Asians and Pasifika are the dominant groups. As a school, we are

acknowledging our students’ cultures in so many ways, in terms of school-wide

activities and learning activities. Besides printing all our cultural greetings

on our school website, class newsletters and bulletins, we have our very own

school karakia in Maori. Every year, our “International Day” is carefully organised

to celebrate everyone’s culture and parents, families and whanaus are also

invited. Our ACE (Academies, Clubs and Electives) program operates once a week

has been set up to recognise and strengthen our students’ cultural interests,

personal skills and knowledge. This program is made up of 25 different ACE groups

focusing on different cultures, languages, dances, music, foods, arts, sports,

life skills and careers-based skills. Some of our ACE groups’ tutors are our students’

parents and whanaus members. Isn’t it amazing to interact with our learners and

work closely with their families? One of my roles is to teach Te Reo Maori

within our syndicate and I use the concept of ‘tuakana teina’ quite often to

empower the students to share their indigenous knowledge and support one

another to achieve their personal and academic goals. Through these school-wide

and learning activities, I have learnt to know and understand my students and

their cultures better. Bishop

in Edtalks (2012) suggests in the video that a teacher whose pedagogy is

culturally responsive challenges the “deficit thinking” of student educability

and has agentic thinking, believing that they have skills and knowledge that

can help all their students to achieve.

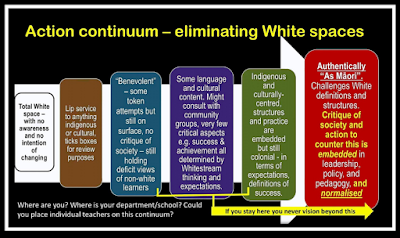

Looking at Dr Ann Milne’s Action Continuum (2017),

I am more in the green block through my experience and current practice.

However, the aspects of education as a colonial tool and is very interesting.

Now what?

Most schools and educational

institutions are ‘mainstream’ with multicultural settings and I personally believe

that it is important for us teachers to have cultural inclusiveness in our practices.

Our pedagogy

should mirror cultural responsiveness in a way to utilise and recognise the

indigenous funds of knowledge within our students and their whanaus. Culture is

important and we as teachers should make extra effort to learn the culture of

all our learners, so we can fully understand who they are and how they learn

without bias. I always expect my students to respect others and their cultures

and I should ‘role model’ that concept and keep in mind that there is always a

room for improvement in my cultural responsive pedagogy.

References

Bishop, R.,

Berryman, M., Cavanagh, T. & Teddy, L. (2009).Te Kotahitanga: Addressing

educational disparities facing Māori students in New Zealand. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 25(5),734–742.

CORE Education.

(2017, 17 October). Dr Ann Milne, Colouring in the white spaces: Reclaiming

cultural identity in whitestream schools. [video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.

com/watch?v=5cTvi5qxqp4&feature=em-subs_digest

Edtalks. (2012,

September 23). A culturally responsive pedagogy of relations. [video file]. Retrieved

from https://vimeo. com/49992994

Gay,G. (2002).

Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education,

53(2),106-116.

Gay, G. (2010).

Culturally responsive teaching (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College

Press.

Milne, B.A. (2013).

Colouring in the white spaces: Reclaiming cultural identity in whitestream

schools. (Doctoral Thesis, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand). Retrieved

from http://hdl. handle.net/10289/7868

Milne, A. (2017). Coloring

in the white spaces: reclaiming cultural identity in whitestream schools. New

York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

No comments:

Post a Comment